SYSTEMS OF LINEAR EQUATIONS

1. Systems of Linear Equations

Linear equations are by themselves not particularly interesting. More often

than

not, one encounters collections of linear equations, involving the same

variables,

which are to be considered simultaneously.

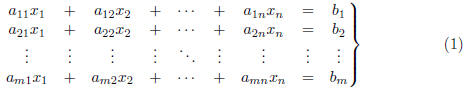

Definition. An m*n system of linear equations is a system of the form

In particular, there are m equations in the n variables x1, x2,

… , xn.

The numbers

aij are called the coefficients of the system (1) and the bi are called the constant

terms.

Definition. A system of equations that has no solutions is called

inconsistent. If

there is at least one solution of the given system, then it is called

consistent.

In particular, note from the definition that a given linear system of

equations

must be either consistent or inconsistent - there are no other possibilities.

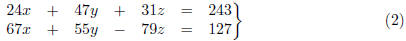

Example 1. The 2*3 system

is consistent. This requires a brief geometric explanation (or a tedious

calculation).

It turns out that the solution set of (2) corresponds to a line in R3. In

particular,

we are asserting that there are infinitely many solutions to the system (2).

Indeed,

the two equations determine two distinct planes in R3 which are not parallel

(their

normal vectors (24, 47, 31) and (67, 55,-79) are not parallel since they are

not

scalar multiples of each other). Geometrically, we know that two such planes in

R3

must intersect each other and that this intersection must be a line.

See Figure 3.5.2 (p.157) of Anton which depicts the

numerous ways in which three

planes in R3 might intersect. Have a close look at this drawing,

since it illustrates

the geometry of all possible solution sets for 3*3 systems of linear equations.

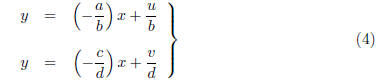

Example 2. Consider the system

where a, b, c, d, u, v are constants and x, y are the

variables. In terms of the familiar

slope-intercept formula for lines in the plane R2, we can rewrite the

system as

and regard these two equations as defining lines l1

and l2, respectively. It follows

that l1 and l2 are parallel (or possibly equal) when they

have the same slope

(i.e., a/b = c/d). This is geometric condition is equivalent to the purely

algebraic

condition

We can summarize this as follows:

(i) If ad - bc = 0, then there are two possibilities:

(a) l1 and l2 are parallel but not

equal (i.e., they are distinct lines having

the same slope). In this case l1 and l2 do not intersect

and hence the

system (3) has no solutions (the system is therefore inconsistent).

(b) l1 and l2 are in fact the same

line and there are infinitely many

solutions to the system (3) exist (the system is therefore consistent).

(ii) If ad-bc ≠ 0, then l1 and l2

have different slopes and hence must intersect

and exactly one point, say (x0, y0). Thus the system (3)

has exactly one

solution (the system is therefore consistent).

Of course, we need no geometry whatsoever to consider the

system (3). Indeed,

you have all solved systems consisting of two equations in two unknowns before.

Nevertheless, thinking about things geometrically often helps our intuition and

helps us "picture things." For instance, now it is geometrically clear why the

mysterious quantity ad - bc arises in the consideration of 2*2 linear systems.

For 2*2 systems of the form (3), the quantity ad - bc is

so important that it

has a special name:

Definition. The determinant of a 2*2 system of the

form (3) is defined to be the

real number ad - bc.

We will discuss the determinants of n*n systems in the

near future. However,

for the moment we would like to concentrate on some qualitative aspects of

linear

systems. In particular, we remark that all of our examples have illustrated the

following (see Theorem 1.6.1 of Anton):

Theorem 1. A system of linear equations either has

no solutions, exactly one

solution, or infinitely many solutions.

It is important to note that the preceding theorem only

applies to linear systems

of equations. Indeed, nonlinear systems can have any number of solutions. For

instance, the nonlinear equation x2 = 1 (i.e., a system consisting of

one nonlinear

equation in one variable) has two solutions. Systems of linear equations are

quite

special { be careful never to assume that something that works for linear

equations

will work for nonlinear equations.

Example 3. If a linear system has two distinct

solutions, then it must have

infinitely many solutions. For instance, suppose that we have a system of 2345

linear

equations in 874 unknowns. If we can find just two distinct solutions to this

system,

then we can (via the theorem) conclude that the system actually has infinitely

many solutions.

The book has numerous examples (see Section 1.2 of the

text) showing how to

find the solution sets for various systems of linear equations. For this class

you will

rarely be required to solve systems of equations larger than 3*3. On the other

hand, it is important to see and do enough examples to gain a level of

familiarity

with linear systems.

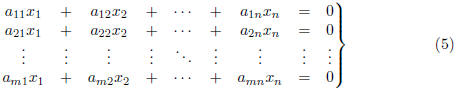

2. Homogeneous Linear Systems

Definition. A system of linear equations is said to

be homogeneous if the constant

terms are all zero. In other words, an m*n (i.e., m equations in n unknowns)

homogeneous system is one of the form

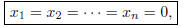

Observe that every homogeneous system is consistent since

the trivial solution

is obviously a solution to (5). Other solutions to the

system (5), if they exist at all,

are referred to as nontrivial solutions.

Since a homogeneous linear system always has at least the

trivial solution, it

follows (from Theorem 1) that exactly one of the following is true for a system

of

the form (5):

(i) The system (5) has only the trivial solution

(ii) The system (5) has infinitely many solutions in addition to the trivial

solution. In other words, the system has

infinitely many nontrivial solutions.

Example 4. Consider the general 2*2 homogeneous

linear system below

The two equations in (6) represent lines l1 and

l2 in R2 which pass through the origin

(0, 0). This corresponds to the fact that a homogeneous system of equations

always

has at least the trivial solution. In fact, the only way that nontrivial

solutions to

(6) can exist is if l1 = l2. This is because l1

and l2 are guaranteed to meet at the

origin - if they intersect elsewhere, then they must actually be the same line.

Recall that if ad - bc = 0, then l1 and l2

have the same slope. Since l1 and l2

have the same y-intercept (namely y = 0) it follows that ad - bc = 0 means that

l1 = l2. In other words:

(i) If ad-bc = 0, then (6) has infinitely many nontrivial

solutions (in addition

to the trivial solution x = y = 0).

(ii) If ad-bc ≠ 0, then (6) has exactly one solution,

namely the trivial solution.

The fact that (6) is homogeneous is crucial here. If the

constant terms were

not both zero, then l1 and l2 could have the same slope

(i.e., ad - bc = 0) yet not

intersect at all (they could be parallel to each other).

Another important fact about homogeneous linear systems is

the following:

Theorem 2. A homogeneous system of linear equations

with more unknowns than

equations must have infinitely many solutions.

It is important to note that the preceding theorem

(Theorem 1.2.1 of the text)

applies only to homogeneous systems (see problem 1.2.28 of Anton).

Example 5. A system of the form

(where a, b, c, d, e, f are constants and x, y, z are the

variables) always has infinitely

many solutions. Indeed, geometrically, the preceding equations represent two

planes

P1 and P2 in R3. Since the system is

homogeneous, both P1 and P2 pass through

the origin (0, 0, 0) - in other words P1 and P2 are

guaranteed to intersect (contrast

this with the inhomogeneous case). This is because the trivial solution

x = y = z = 0

is automatically a solution to both equations in the

system (7). Geometrically, we

can see that either P1 = P2 or P1 and P2

intersect in a straight line. In either case,

there are infinitely many solutions to the system (7).

|